Perpendicular to the moving object (Einstein's light clock)

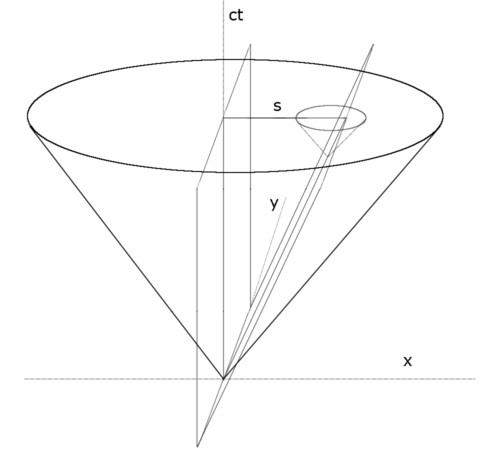

In Minkowski space, S moves in the x-direction. A plane perpendicular to x is supposed to intersect the light cone at the origin. This plane rotates around the y-axis with S by tan(beta) = s/ct = v/c. This rotated plane intersects the respective future cone of S at its apex. The conic section is always two intersecting lines. The projection onto the x-y plane yields the angle cos(alpha) = v/c to the x-axis in the direction of motion.

In Sexl's book, on page 107, the formula tan(e) = sin(e')*sqrt(1-vē/cē)/(cos(e')+v/c) is given. Setting e' = 90°, we get: tan(e) = sin(e)/cos(e) = 1*sqrt(1-vē/cē)/(0+v/c). With sin(e) = sqrt(1-vē/cē), we then have cos(e) = v/c.

From the observer's perspective, perpendiculars of moving objects appear oblique, and those of accelerated objects appear curved (Einstein elevator).

Ludwig Resch